When journalists are called to cover a suspicious package, a discovered pipe bomb or a suspected improvised explosive device, whether handheld, vehicle-borne or otherwise, the assignment carries extreme risk.

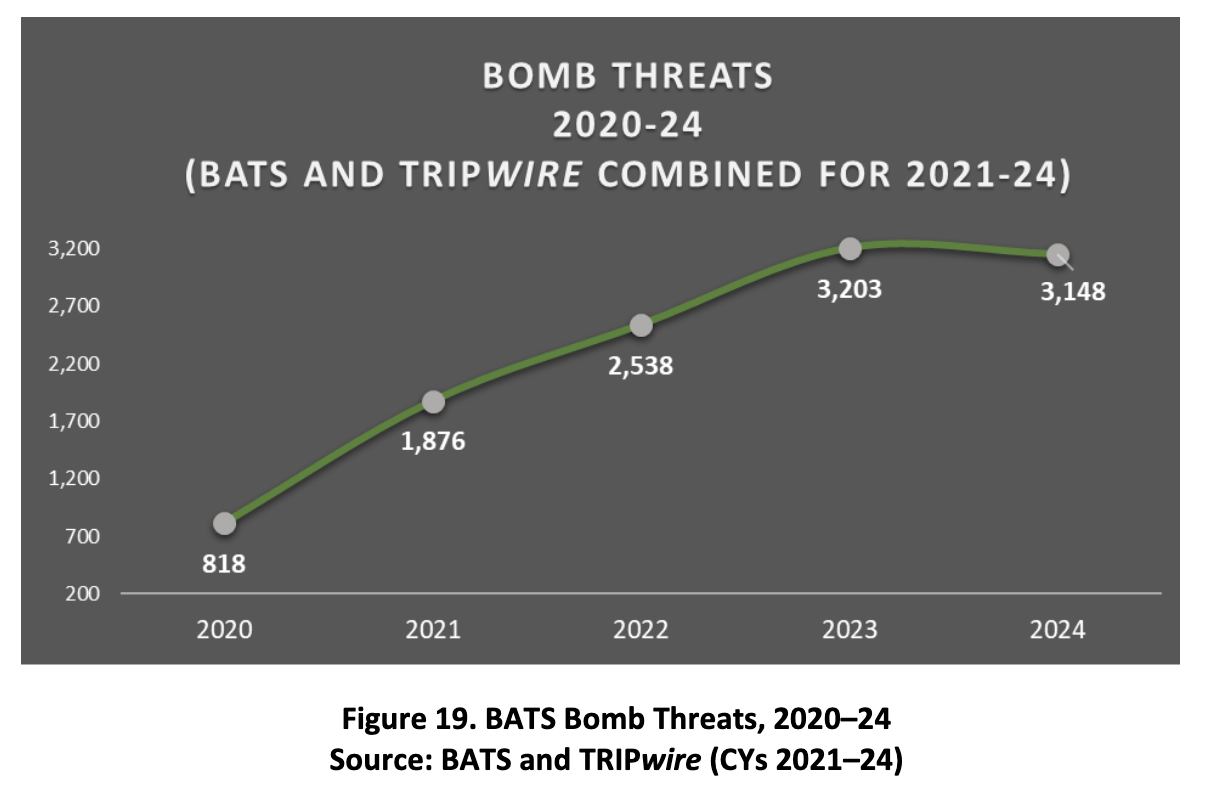

According to data from the U.S. Bomb Data Center (USBDC), “in 2023, there were 3,203 reported bomb threat incidents That represents a 26% increase over the previous year.” In 2024, a slight decrease was noted contray to longer trentds. Understanding the hazards, the law enforcement response and protective measures is essential to staying safe. Extreme caution should be exercised before responding to an explosive-related event. Newsrooms should have protocols and procedures in place with clearly defined expectations for journalists before any such assignment.

The Primary Hazard: The Blast

The central hazard of any explosive device is the blast wave. The blast wave is a rapid, high-pressure shock front that moves faster than the speed of sound. This overpressure can cause catastrophic injuries. The U.S. Department of Defense defines blast injuries as “a complex type of physical trauma resulting from direct or indirect exposure to an explosion. Blast injuries range from internal organ injuries, including lung and traumatic brain injury (TBI), to extremity injuries, burns, hearing, and vision injuries.”

The closer to the device, the more lethal the blast. Importantly, no one can hide from a blast. Ordinary objects, car doors or walls may not provide protection. The pressure wave can travel around corners, through openings and can collapse light structures. True safety comes only from distance and substantial cover such as reinforced concrete, and even then only at recommended standoff distances.

We label this as primary because hazards associated with blast waves are far more difficult to mitigate. Protective equipment offers little defense, and the only sure safeguard is maintaining distance.

In this video, the blast wave propagation is visible ahead of the fire and fragmentation.

Secondary Hazards

Explosive incidents rarely involve the blast alone. Journalists must also account for:

Fragmentation: High-velocity projectiles launched outward. These are often more deadly at greater ranges than the blast itself. This may include shrapnel from the device casing or surrounding environment.

- Primary fragmentation: Shards of the device itself. This may include nails, ball bearings or casing fragments intentionally included to increase lethality.

- Secondary fragmentation: Environmental debris including glass, rocks, metal or wood propelled outward by the explosion.

Thermal hazard: Fire, burns or secondary fires ignited by the explosion.

Structural collapse: Glass, masonry or building debris displaced by the shockwave.

Chemical hazard: Some devices incorporate toxic chemicals.

Follow-on attacks: Secondary devices deliberately placed to target responders and bystanders.

Hoax Devices

Not every suspicious item turns out to be an explosive. Hoax devices are packages deliberately built to look like bombs but without any explosive material inside. They may contain wires, pipes, batteries or clocks placed to provoke fear and trigger a law enforcement response.

It is important to distinguish between a false alarm and a hoax device. A false alarm occurs when a harmless item such as a forgotten bag, toolbox or package appears suspicious but was never intended to imitate an explosive. A hoax device, in contrast, is deliberately constructed to look threatening and cause disruption. Both trigger the same cautious law enforcement response, but a hoax device involves criminal intent while a false alarm does not.

Hazards to journalists:

- False sense of safety: A hoax can condition reporters to take future threats less seriously, increasing risk later.

- Scene hazards: Law enforcement will treat the device as real until proven otherwise, meaning journalists are still exposed to potential evacuation, cordons and tense crowd situations.

- Operational hazard: Hoax devices can drain police resources, leaving other areas less protected.

Always treat a suspected device as real until authorities declare otherwise.

Come-Along Incidents

A come-along incident occurs when a minor suspicious event, such as a small package, loud bang or false report, is used to draw in first responders, journalists and the public, only for a second, larger device to be detonated. These have been used by terrorist groups worldwide to maximize casualties.

Hazards to journalists:

- Secondary devices may be hidden along the routes where media and responders naturally gather.

- False sense of “all clear”: After an initial disruption, reporters may edge closer, only to be caught by the real threat.

- Crowd vulnerability: Media clusters are predictable targets.

Never assume the first device or incident is the only one. Always remain aware of secondary threats.

A US Army Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technician interrogates a suspected vehicle borne improvised explosive device during a training exercise at Fort Sill, Okla., Dec 2018. (U.S. Army photo by Staff Sgt. Lance Pounds, 71st Ordnance Group (EOD), Public Affairs)

Radius of Hazard

The effective danger zone depends on the size and type of explosive:

- Small pipe bomb: Fatal radius may be 30 to 50 feet, but fragmentation can injure out to 100 to 150 feet.

- Backpack-sized IED: Blast and fragmentation effects may extend hundreds of feet.

- Vehicle-borne IED (VBIED): Can create a lethal radius of hundreds of yards, with glass breakage extending more than a quarter mile.

- Hoax devices: May create no physical blast hazard, but operational disruption and crowding can still pose danger.

Distance saves lives. Never assume a small package means a small hazard.

Protective Distances

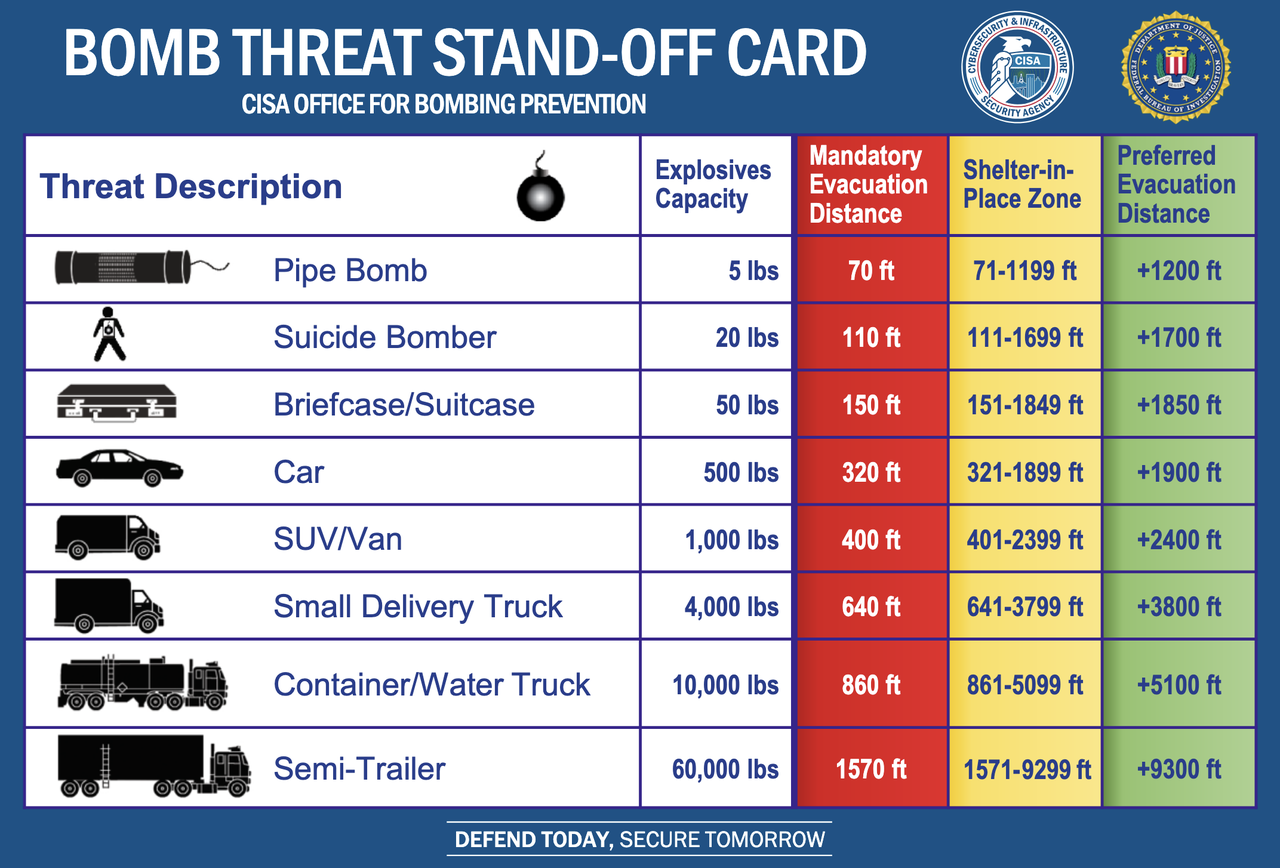

While exact distances vary by device, the Department of Homeland Security offers general evacuation guidelines:

- Small devices (pipe bombs, grenades, small satchel charges): Minimum 1200 feet.

- Suicide belt/backpack: Minimum 1,700 feet.

- Small vehicle (sedan/truck): Minimum 1,900 feet.

- Large vehicle (delivery van/semi-trailer): 2,400 to 5,000 feet or more.

Journalists should remain behind law enforcement barriers whenever possible and never push closer for the shot.

Law Enforcement Response Procedures

When an explosive hazard is reported, journalists should anticipate:

- Establishing a cordon – Police set an inner and outer perimeter to control access.

- Evacuation – All civilians, including media, are moved out of the hazard area.

- EOD (bomb squad) response – Explosive Ordnance Disposal technicians will use robots, protective suits or remote tools to assess and neutralize the device.

- Secondary device sweeps – Areas are checked for additional explosives, especially in suspected come-along incidents.

- Controlled detonation or render safe – The device may be disrupted in place or transported.

- Post-blast or hoax investigation – The scene is treated as a crime scene, whether the device was real or a hoax.

Journalist Precautions

Covering these events is not the same as covering a fire or accident. Journalists must:

- Respect the cordon: Never cross a barrier, even if police are not immediately present.

- Keep distance: Follow DHS distance guidelines. If you can see the device clearly, you are too close.

- Stay behind hard cover: If possible, position yourself behind a building corner, concrete wall or other substantial cover, not glass windows.

- Watch for secondary devices: Be mindful of bags, boxes or unattended items near your position.

- Stay alert to come-along risks: If an initial incident appears resolved, stay vigilant for secondary threats.

- Avoid clustering: Do not gather with other media in predictable groups close to the perimeter. Be cautious around designated media briefing locations — these spots can become predictable gathering points that may be vulnerable if a secondary device or come-along incident occurs.

- Follow instructions: Obey law enforcement evacuation or movement orders without delay.

- Plan communications: Ensure your editor or newsroom knows your location, your distance from the scene and your reporting plan.

- Protect your hearing and eyes: Ear protection and shatter-resistant eyewear can help reduce injury if an unexpected detonation occurs.

Final Word

Explosives, whether real, hoax or part of a come-along ploy, are unpredictable. No story is worth your life. A journalist’s responsibility is to bear witness, but survival depends on respecting distance, recognizing the hazards and allowing professionals the space they need to work safely.

About the Author

This report was authored by Bryan Woolston, managing director of Crisis Ready Media. Woolston is a photojournalist with more than a decade of experience covering breaking news, politics and conflict for major international outlets. He served 20 years in the U.S. Army as an infantryman and Explosive Ordnance Disposal technician. He received extensive training and has operational experience in identifying, rendering safe and disposing of explosive hazards, including improvised explosive devices, and chemical, biological and radiological threats. He brings both frontline military expertise and newsroom perspective to the subject of explosive hazards and journalist safety.